|

Yet his mind certainly works in Cinerama and his guitar often speaks in

tongues. Knopfler's 1983 soundtrack for the Bill Forsyth film Local Hero

conjures up vivid images of the Scottish Highlands with its pensive

melodies and the solitary sigh of his guitar. His lyrical soloing on Dire

Straits, the group's 1978 debut album, resonates with animated echoes of

moaning cotton-field blues, Nashville plucking and gutsy Sun rockabilly.

His singing is a smoky mumble, but it renders his rich lyric portraits of

young lovers ("Down to the Waterline") and jazzmen ("Sultans of Swing")

with seductive intimacy.

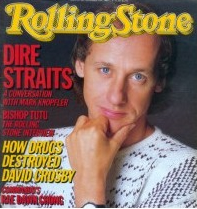

Born in Glasgow, Scotland, in 1949, Mark Knopfler is the son of a Jewish

architect whose communist sympathies forced him to flee the fascist regime

in his native Hungary. When Mark was about nine years old, the family

moved to Newcastle, in the north of England. At fifteen, he got his first

guitar. Not long after, he cut his first record in a London studio, an

unreleased demo of an original song, "Summer's Coming My Way."

Knopfler worked for two years as a cub reporter at the Yorkshire Evening

Post and, after graduating with an English degree from Leeds University,

was a lecturer at Loughton College in Essex. In April 1977, he moved into

a London apartment shared by his younger brother David and bassist John

Illsley. With the addition of drummer of Pick Withers, they became Dire

Straits.

The pressures of the group's sudden success - they got BBC airplay with a

demo of "Sultans of Swing" and had a record deal by Christmas 1977 -

eventually ripped the band in half. "David was under a lot of strain,"

says Illsley. "Mark felt very responsible for David and didn't quite know

what to do. But Once Making Movies was out and David had left, it seemed

to lift a tremendous strain. Mark felt very freed." Withers also quit, in

1982.

With his second wife, the former Lourdes Salamone (he was briefly married

during his university days), Knopfler splits his home life between

apartments in New York's Greenwich Village and London's West End. But he

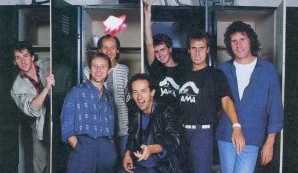

isn't seeing much of either this year. The current seven-member Dire

Straits is in the middle of a mammoth world tour that will not end until

next April.

|

|

Was stardom something you actively pursued? Oh, no. That's a

byproduct of a love affair with a guitar and wanting to be in a band and

make music. I always wanted to be in a band. I used to draw pictures of

bands when I was a little kid in school. I used to draw pictures of

guitars all day. I used to go and watch a guy in the woodwork room making

a guitar, just so I could hold it. I pestered my dad for years and years

until I got a cheap imitation one. It was a red imitation Stratocaster. He

bought it for me on my fifteenth birthday. It cost fifty pounds, which was

a lot then.

Were your parents musically inclined? They can both sing in tune.

My father tried to teach me piano and violin. He tried the piano when I

was six, but I wouldn't bother reading the music. I would just play by ear,

and as soon as it got difficult, I was in trouble.

But then I heard my uncle Kingsley play boogie-woogie when I was about

eight years old. That was one of the most beautiful things I had ever

heard. Those three chords, the logic of it. So I just used to slam out

boogie-woogie on the piano, drive everybody nuts.

How did you do with the violin? I was about thirteen. I could get

great-sounding notes out of it, but don't ask me to read music. I tried

the saxophone a couple of years ago, but it's so much tied in with reading

that it's impossible for me. I go by my ears. I can't relate music to

those dots.

I found out more about music in the past few years just by studying chords.

You learn them the same way you do words. You hear a long word and you

know what it means just by its usage. Your vocabulary increases. The same

way with chords. I can recognize music now that I couldn't have four years

ago.

What was your first band? It was just school friends playing at

somebody's house. Then we played a couple of school dances.

When I left university, I went down to London and got in this band called

Brewer's Droop. I was with them for maybe two months. They were sort of an

obscene R&B Cajun outfit. Brewer's droop is something that you suffer from

when you've been drinking too much and you can't get it up.

They actually had a deal with RCA that was just falling apart when I

joined them. But I did a bunch of gigs with them. That was my first taste

of playing on the college and big-clubs circuit. I did a little bit of

recording with Brewer's Droop at Rockfield Studios. I don't think any of

it ever came out.

After that, I just starved to death, basically. It got pretty tough until

I got hold of this teaching job that saved my life. Then I had a band

called Café Racers, which was the name of a kind of motorcycle, not a

particular make, just a customized street bike. We played around the pubs

and the college where I was teaching.

You also worked as a journalist, even dabbling in music criticism.

A girl I knew, her big brother was a newspaper reporter, and I thought, "Oh,

he seems to be having an interesting time." I started out with nine pounds,

eighteen shillings and three pence a week [about $23.75 at the time].

What sort of music did you review? Local bands, some of the big

bands that came to town as well. The last story I ever wrote for the

newspaper - on the day I left - was the death of Jimi Hendrix. I was in

the press room at Leeds Town Hall, 'cause I'd been covering the courts all

day, when the news editor came in and said, "Hello, lad, Jimmy Henderson

or Jimi Hendrix or whatever the bloody hell he's called died. Did you know

him? Well, we haven't got any time. I'm putting you straight onto copy." I

was stunned. I don't recall what I wrote. I said some stuff, left the

paper and got drunk.

How did you get back into rock & roll after you quit teaching? It's

amazing what I've done to get into bands - hitchhike up and down the

country with a heavy electric guitar, getting on buses with two guitars to

go up to an audition. I remember once hitchhiking home up to Newcastle on

Christmas Day from the other end of the country, the snow all around,

nobody on the roads, with a guitar and a bag, standing in the middle of

nowhere. You've really got to want to do it.

For me and John, in the early stages of the Dire Straits thing, there was

a collective willpower that went into it. If you're a lazy son of a bitch,

you're just going to sit around and complain 'cause there's nothing

happening. We weren't.

Your songwriting has undergone a major shift in recent years, from the

evocative, atmospheric quality of "Wild West End" and "Down to the

Waterline" to the simpler, more direct verse on Brothers in Arms. What

inspired that change? I'm not saying I've had it with ambiguity or

that things can't be multi-layered. I've just become more drawn to writing

those kind of songs, where there is no problem in terms of who's singing

what. If I listen to Willie Nelson sing "Blue Skies", it always strikes me

as great, very simple and direct.

Sometimes it's better to go for the big, broad, beautiful statement rather

than start getting involved in all this ambiguity. I think "Born in the

U.S.A." is a classic example. Even Reagan can come in and invoke the

spirit of Springsteen and couple him with Rambo. Bruce is trying to say, I

think, that there's absolutely nothing wrong with loving your country, and

there's nothing wrong with good citizenship. But the meaning has been

taken and distorted by outsiders and used for their own purposes. I

certainly don't want Reagan coming onto my songs and using them. I'd

certainly have something to say to him about it if he tried, too.

The layers of irony in "Money for Nothing" have certainly confused

people. I got an objection from the editor of a gay newspaper in

London - he actually said it was "below the belt." Apart from the fact

that there are stupid gay people as well as stupid other people, it

suggests that maybe you can't let it have so many meanings - you have to

be direct.

In fact, I'm still in two minds as to whether it's a good idea to write

songs that aren't in the first person, to take on other characters. The

singer in "Money for Nothing" is a real ignoramus, hard hat mentality -

somebody who sees everything in financial terms. I mean, this guy has a

grudging respect for rock stars. He sees it in terms of, well, that's not

working and yet the guys rich: that's a good scam. He isn't sneering.

How did you write "Sultans of Swing"? John Illsley says that on an

early tape you made of the song, it actually had more of a lilting,

country-and-western feel. It had a completely different musical thing

to it. I wrote it on an acoustic guitar. Then when I started playing it on

the Strat, it came out different, just because I was using a different

guitar.

I actually saw a jazz band one night in south London. It reminded me that

whenever a band plays something like "Creole Love Call", you realize how

beautiful that music is. It's important to listen, to know about that

music. It doesn't matter if it's Ellington or a traditional jazz band or

Roland Kirk who plays it. It's fine music.

What about "Tunnel of Love," which is more complicated in terms of its

length and arrangement? It's in different sections, but there's a kind

of logic to it. It seemed like it needed that breakdown section in the

middle with the drums, trying to convey the big swinging movement, the

screaming and the noise. It all stems from extending an idea. You can use

circus music as a device to put you there, where there's a smell and a

feel, a geography where people can have their own little movie.

Is there a big difference between making those little movies and doind

film soundtracks? Ry Cooder has said he feels his best music is on

sountracks, not his albums, because he thinks he's freed from constructing

a three-minute single. Do You ever feel that way? I can understand

what he means, but I've never felt constrained like that when I'm making a

commercial album.

It's a bit more complicated doing a film. It all depends on how much

technical knowledge you've got - I have very little.How much diplomacy

you've got. How much of a musician you are. How much of an administrator

you are - and I'm zero at that. Then, too, directors are different. I've

worked with only two, Bill Forsyth and David Puttnam. They're completely

different in their feeling about music, about where they want it in a

scene and how much. Some directors know down to the second how much they

want, and others are very vague.

What was it like co-producing Bob Dylan's Infidels album? I met him

the first time we played Los Angeles. He Came down to see the band, and

then I started going out to Santa Monica, where he had a place, and we

would run down his songs for Slow Train Coming.

For Infidels, I was in the studio in New York, set up to do Local Hero.

Bob wanted Sly [Dunbar] and Robbie [Shakespeare] and Mick Taylor, so we

got them. Neil Dorfsman [co-producer of Brothers in Arms] was the house

engineer at the Power Station, and I had Alan [Clark, Dire Straits'

keyboardist] over. We had a little house band. Because Bob had been at my

house a few times to run down the stuff, it was usually easy to get

something on tape. Because with Bob Dylan, he's not necessarily going to

be around more than two or three times.

There have been a lot of personnel changes in the band, and one hears

you're a stern taskmaster. Do you think you are? No. That's one of the

things you can't win. If you are, you're a dictator. If you're not, you're

a wimp. Ninety five percent of the time I like being the fearless leader.

I just think that when you write a song and get it together, you want to

get it done right. Now if that sometimes involves making people work long

hours in rehearsals, that's fair enough.

Sometimes, I make the mistake of stopping and waiting for somebody else to

give, waiting for somebody else to show how much they care. I've done that

a few times, and I don't think it gets you very far.

|

|

What is there left for you to learn about the guitar? The thing

about my guitar playing is that I don't know much about it. It's a process

of always learning stuff. I recently went down to Nashville to play with

Chet Atkins on an album he's making of duets with other guitarists. I

could have stayed there for five years. I loved it and learned so much. So

it never ends, what you need to learn. In terms of my vocabulary with the

guitar, I think I can say, "Hello, how are you?" and that's about it.

I basically feel that as long as you have soul and you have melody, then

it doesn't matter whether you're Miles Davis or Waylon Jennings. You're

going to make great music. Often, you find that very advanced, trained

musicians love and adore players with very little technique at all, and

that's as it should be.

Have you ever released an album and then thought, "Boy, that was a step

in the wrong direction. I wish I hadn't put that out"? All of them.

All of them? Oh, yeah. I don't like them that much. The best stuff

happens when you're just sitting around playing, by miles. I don't like to

sit around listening to my own records - it's perverse. I think in general

that there's too much attention paid to albums just because of this

business that's grown up around it. I'm going to be playing better stuff

than anything on my records if I get up in a tiny bar and play with a bar

band.

As rock stars go, you seem to be all work and no play. Would you say

you're a workaholic, that you do music to the exclusion of all else? I

wish that wasn't the case. Because I like all the things guys like. You

know, I love to eat and I love to sleep. I love to watch sports, I like

cars. But when you're touring so much and doing all these things, it ends

up that you haven't got time to put in new light bulbs all over the place.

I just don't get off on painting the toilet.

I get accused of being lazy. I'm lying on the bed, watching sports on TV,

and Lourdes wants me off the bed, she wants to tidy up around me. I end up

getting thrown out of the house. You have to do something, right? So why

not go do a session?

|